In my large and extended family, I am one of the oldest. As a result, I had spent more time with our older family members and they had told me stories…

I had been considering memorializing those stories when I was asked to share those I knew about our Mother’s childhood. But I realized in order to understand who our Mom was as a child, I needed to go back to her mother’s childhood…

The following stories are based on the things I was told, but expanded with historical accounts of the times, places and people; and merged together with some story telling and some imagination. I hope you enjoy it.

I. Alice: A. Endings and Beginnings

1917. THE TELEGRAM

The sound of the car stopping in front of the farmhouse was lost amidst the noise of the two women working in the kitchen, and the low sound of the fires burning in the kitchen stove and the potbelly stove in the living room, unnoticed that is except for the hound dogs on the porch who started baying and barking according to their nature.

Mama Perdue wiped her hands on her apron and looked meaningfully at her oldest daughter. If the visitor to the remote farmhouse represented danger, it would be her responsibility to run out the back door and find her father.

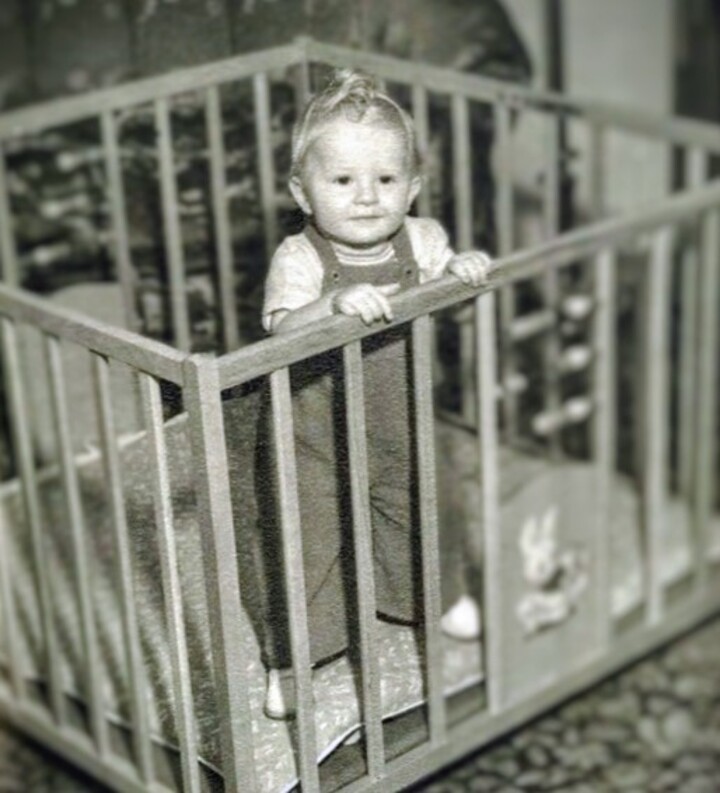

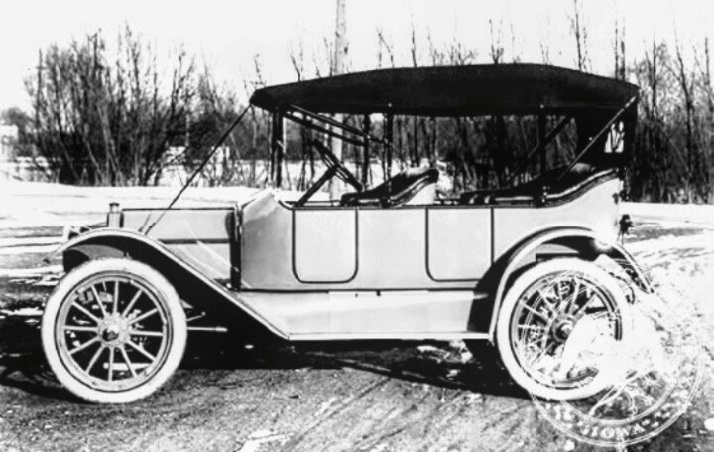

As she passed through the living room, Mama Perdue glanced over at baby Charlie in his playpen in the corner, holding onto the railing, shaking back and forth, and adding ‘Uh, uh, uh!’ as he did every time the dogs made a ruckus. She walked to the front door, opened it and looked through the screen door at the car stopped in front of the house. The driver moved over to the passenger side and waved at her. It was then that she recognized the distinctive cap of the town’s telegraph operator.

Stepping out on the cold porch in her slippered feet, she shushed the dogs, some coming over to sniff her hands for food. After all of the hounds were sitting and silent, the uniformed man got out of his vehicle and slowly walked over to the steps. The hounds were looking at the stranger with interest, but none showed any hostile intent. So, just as slowly, he walked up the stone steps to the wooden porch and Mama Perdue.

“Will you come in?” she politely offered. They both came in from the cold into the almost sweltering heat of the wood-burning stove where he took off his scarf and jacket, hanging them on a convenient peg, but kept his distinctive, identifying cap on.

Mama ushered the man to their best stuffed chair and asked if he would like some water. The wells in Stokes County were dug down to fractured granite bedrock and produced some of the sweetest water anywhere. The telegraph xterm murmured a “Yes, please,” and a nod from Mama sent Nona, peeking around the kitchen archway, to pour a glass from the bucket. A questioning look at her mother was met with a negative shake. Mama’s throat was so tight from apprehensive dread of the message the man had brought that she doubted she would have been able to swallow anything.

After taking a long drink of the water and sighing with satisfaction, the man stated the nature of his business. “Ma’am, you and Mister Perdue have received a telegram. Would you like it now, or would you prefer to wait for Mr. Perdue?”

“Wait,” Mama managed to croak out. “Nona?” She called to her daughter again, but Nona knew what her mama wanted and needed no further instructions.

She quickly walked over to the pegs by the door, winding her long, loose pigtails around the top of her head and pinning them in place with a pair of old and worn knitting needles she pulled from her capacious apron pocket. This was the only winter cap she had. She pulled an old and worn coat from its peg, obviously too big for her slight figure, but underneath it could be seen a length of rope hanging on the peg.

Next she slipped her feet into an old, worn pair of boots, also obviously too big for her stockinged feet, but inside they were stuffed with pages from the Christmas catalog, which was just about the only mail they received from the outside world.

Cinching her coat around her narrow waist with the rope, Nona squeezed through the door quickly to keep the heated air inside and the winter cold outside. Her boots could be heard clumping loudly across the wooden porch, then their sound quickly faded in the distance.

Mama Perdue looked toward the telegraph bearer, knowing the social situation called for polite conversation, but she just couldn’t find any words to say. The old man seemed to know what she was feeling as he politely kept his gaze turned away from her, occasionally sipping from his glass of water.

Despite not knowing yet what the telegraph said, Mama Perdue had a good idea. Earlier that year, her two oldest boys, Stanley and John, had to register for the draft. Stanley, the oldest, had married a girl across the other side of the county, Bessie, and they already had two children. He had taken over her elderly father’s farm and it would have been a hardship to their family if he was drafted.

But John, her favorite son, as yet unmarried, but with plenty of prospects, was drafted instead. Not her John! The best and brightest of her children. His smile could light up any room. When he laughed, everyone wanted to laugh with him. He was her best hope for becoming something more than a farmer. ‘Not her precious John!’ She wailed inside.

She was disturbed from her reverie by baying from the hounds on the porch that was quickly shushed. Then there was the clump of boots across the porch and the door was flung open. Standing there was her husband, his axe held in both hands and a look of menace in his eyes. When he saw the reported Western Union man and his wife sitting calmly on opposite sides of the living room, although now wearing startled looks, and his baby son was screwing up his face like he did just before he started crying. Papa mumbled an apology and stepped fully into the house, followed by their tall first son, also holding his axe as if expecting an attack, then Nona, her face red and breathing harder than the two men as she had run the distance twice.

Papa Perdue leaned his axe against the wall and motioned his two children out of the way, so he could shut the door. He then took off his coat and scarf, hanging them on a peg, then stooped down to unlace and remove his boots. The other two quickly followed suit. A whispered exchange with Nona sent her into the kitchen to emerge a moment later with two glasses of water.

Papa had gone to stand next to his sitting wife, a hand on her hunched shoulders. Stanley had sat down in a nearby chair when she came back with their waters. Nona slipped back into the kitchen for her own water, then returned to stand next to the comforting presence of her big brother.

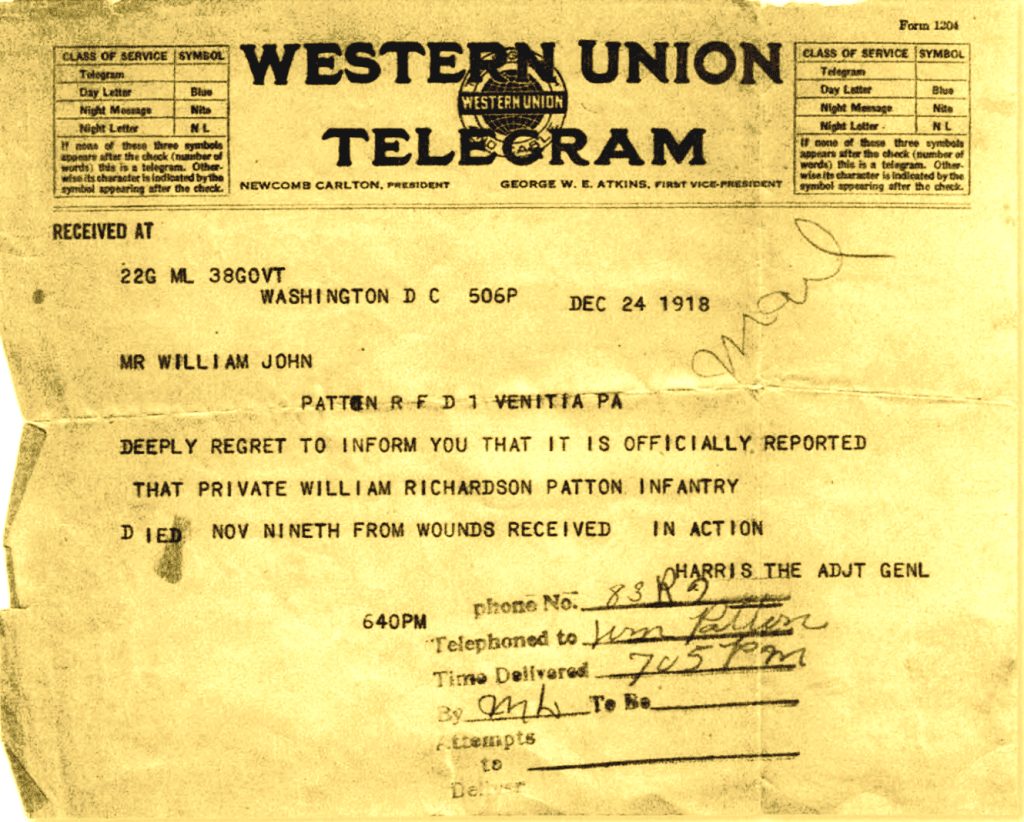

Seeing that all were ready, the man reached into an inner pocket of his vest and pulled out the distinctive yellow Western Union envelope. Standing and repeating his formal words, “Mister and Missus Perdue, you have received a telegram,” he stepped over and handed it to Papa Perdue, before returning to his seat.

After a suspicious look at him from under his lowered brow, Papa looked at the envelope for a moment before reaching into his pocket and retrieving his pocket knife. Outwardly appearing calm, his nervousness was betrayed by the shaking of his hands as he snicked open the longest blade and slit open the envelope. He too knew what the telegram probably meant.

Papa stared at the words on the page, but neither he nor his wife could read, being surviving children of the Civil War. Their families had been more concerned with hiding their farm and stock from the marauding bands of foragers from both sides to do more than see that they had enough food to eat.

Hearing that logged out, arable farming lands suitable for growing tobacco were being granted in North Carolina, they had married and moved south from southwest Virginia, driving a wagon with gifts of the tools needed to start their own farm, even if some were second-hand.

Since slavery had been abolished, the big plantations had failed and been parcelled out. Now tobacco commerce relied on small farms near enough to a train depot they could take the cured tobacco there by wagon to be bid on. At the train depot in Stokesdale, there were agents from American Tobacco to the east in Reidsville, and from the west at R.J. Reynolds in Winston-Salem, so the area growers almost always got premium prices for their cured tobacco.

But his children were more fortunate than their mama and papa. Here in this time and this place, their children had been able to go to school, to learn to read and write, to handle numbers, to learn more about the bigger country they lived in, and even about the greater world beyond. Although he didn’t want to pass this responsibility on to his oldest daughter, he held the telegram out to Nona.

After a brief look of panic, Nona took the yellow page, unfolded it, cleared her throat and started reading.

MR AND MRS PERDUE

GENERAL DELIVERY

STOKES COUNTY NC

DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU THAT IT IS OFFICIALLY REPORTED THAT PRIVATE JOHN PERDUE INFANTRY DIED NOV FIRST FROM WOUNDS RECEIVED IN ACTION.

Mama Perdue wailed as her worst fears were realized and buried her face against her husband’s side, wrapping an arm around his waist to hold him close, while her body shook with her sobs. Stanley was white-faced from the shock. Nona suspected she was too as tears ran down her cheeks. She saw that even her staid father’s cheeks glistened with shed tears as he tried to comfort his wife.

Her mother’s sobs grew louder as she lifted her face from her husband’s side. She held our her free hand to Nona with a grasping motion and the girl realized she wanted the telegram. Nona placed it in her hand and Mama crushed it to her chest as the last tangible reminder of the son she had lost. Her wails redoubled and she pressed her face against her husband’s side again to muffle them.

Baby Charlie had started crying too with his mother’s wailing, so Nona went over to his crib, picked him up and started bouncing the tot on her hip, whispering shushing sounds to try and calm him.

The bearer of bad news stood up, and formerly asked, “Mister Purdue, may I be of any further assistance?” Papa looked up and tried to answer, but found he could not speak past the lump in his throat, so he just shook his head ‘no.’

“If not sir, madam, then I take my leave of you.” Papa just nodded a ‘yes’ and the telegraph operator walked over to the door, pulled his coat and scarf from its peg and put them on against the cold he knew was waiting for him outside.

Opening the door slowly, he carefully looked at the hounds on the porch through the screen door. When they showed no particular interest in him, he exited, closed the door behind him and carefully walked to his car. Turning it around in the barnyard, he headed back to town.

The old man had been delivering all too many of these death notices lately. He felt he should deliver these in person to the good folk of Stokes County, rather than giving them to his assistant to deliver on his bicycle. He hoped that by delivering them in person–a venerable man, dressed in the Western Union uniform–he communicated that he cared about their grief as they received the bad news about their sons, their husbands, their brothers, their fathers…

As he drove down the dirt road leading back to the highway, he saw a child, heavily bundled against the winter cold, walking towards him. He slowed down and she stepped off to the side of the road to let him pass. He gave a brief wave as he passed by.

Looking in his rear view mirror, he saw she’d turned and was watching as he departed. Abruptly, she turned back toward home, breaking into a shambling run, apparently realizing something had happened.

Alerted by the whining and excited yipping of the young hounds who her sister had played with growing up, Nona rushed to the door from the kitchen to intercept Mamie as she came in. Just as she approached the door, little Mamie burst in, out of breath and her cheeks red from the cold. “Nona! I saw this man in a car, who was he?” Nona quickly shushed her little sister and motioned for her to shed her winter gear. Baby Charlie added his, “Uh, uh, uh!” to the hubbub and Nona stepped over to calm him down too.

As little Mamie walked across the living room, she could hear sobbing coming from their parents’ bedroom. Just as the excited girl was about to ask what was wrong with mama, Nona stepped over and placed her finger against the smaller girl’s lips and shushed her again, ushering her into the kitchen.

Warning little Mamie in a whisper to speak quietly, Nona poured her a glass of water and told her in whispers who the man in the car had been and the bad news he had brought of their brother John’s death in the War.

“But where’s Papa, shouldn’t he be here?” Whined the little girl. Shushing her little sister again, Nona explained that their big brother had driven his wagon over to help chop down and chop up the old, dead oak tree on the other side of the southeast field. It was getting late on this winter day, so the men had rushed back to load up Stanley’s wagon with the big limbs they had already trimmed from the trunk so he wouldn’t have to return home empty. Also, he wanted to get home before dark, if he could, although he carried a kerosene lantern to light his way, if he needed it.

Little Mamie whined another question, “But what does it mean?” Nona realized her little sister wasn’t quite old enough yet to understand, so she explained it this way, “Our brother, John, is never coming back from the War and that makes Mama very, very sad.”

“But why?” The little girl whined again. Nona shushed her and reminded her to keep quiet, then cautioned her, “Just remember, talking about John makes Mama very, very sad. So, don’t ever mention his name again and don’t ever ask her about him.”

* * * Historical Note * * *

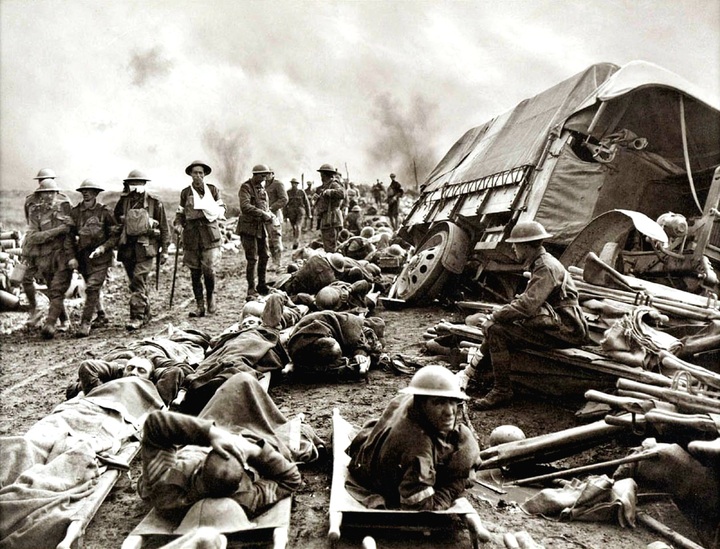

Our Great Uncle was most likely killed in one of the pivotal Fall 1917 WW1 campaigns, featuring the brutal Third Battle of Passchendaele in the West Flanders region of Belgium.

The Third Battle of Passchendaele was characterized by devastating mud from the heaviest rainfall in the region in 30 years…

…and by high casualties–up to 700,000 men were killed or wounded.

* * *

1918 NEW LIFE

Mama Perdue spent the rest of the Winter in bed, leaving care of Mamie and baby Charlie to her oldest daughter. This worried Papa, but he hoped that his wife would eventually pull out of her depression, so he cautioned everyone to just walk softly and speak quietly.

Spring returned to the farm with a burst of warmth, the bright colors of flowers and the sounds of songbirds in the trees. Papa had been trying to coax his wife to return to farm life, but the natural renewal of life that was Spring seemed to present a more powerful argument.

Starting with breakfast and continuing for each meal over the next week, he helped his wife out of bed and helped her walk around the house, then the porch, then the yard, further and further each day as she regained her strength.

One of the arguments he had used to motivate her was they should have another son to replace the one they had lost. There came a day a few weeks after Mama had fully regained her strength when she quietly told him, “I am with child.”

Spring turned into Summer with the swelling fruit of the plants on their farm and the swelling fruit of his wife’s womb. Things had returned to normal on the Perdue farm…almost.

Papa noticed his wife was much quieter, rarely joining in the frivolity around the kitchen table as everyone recounted the pratfalls from around the farm that day. Papa would sometimes find Mama just staring off in the distance at nothing, completely oblivious to what was going on around her. Papa worried, but he didn’t know what else he could do.

The worst was on John’s birthday. After breakfast, Mama went back into their bedroom, took the crumpled and tear-stained telegraph out from the little treasure box of their cedar chest, smoothed it out and just started crying, holding it to her chest, rocking back and forth in her grief. Papa made sure Nona had the children in hand and told them, “Mama is remembering your brother John today, and she is very, very sad. Walk quietly around the house today and I am sure she will be fine.”

Little Mamie listened with big eyes and nodded solemnly. Nona wore a haunted expression, her own legacy from that tearful day. Baby Charlie continued chortling contentedly from Nona’s lap, playing with his feet.

Work around the farm necessitated Papa get busy, but he was reassured when he returned for lunch and found Mama back at work in the kitchen.

* * *

1919 BABY ALICE

There came a cold clear day in the middle of January, 1919, a little over a year after that fateful telegram, when Mama’s birth pangs came upon her. For the births of her previous children, Mama had the neighboring farmwife over to help with the delivery. Since her deliveries had been routine after, Stanley, her firstborn, Mama felt it was time for Nona to learn some of the things about having babies, since she was now of marriageable age, so she drafted Nona as an apprentice midwife.

Papa took care of the younger children in the kitchen, boiled water for washing, and stayed ready to ride the mule to the neighbor’s farm if anything went wrong.

There was much grunting and some screaming heard from the master bedroom over the next few hours. Baby Charlie didn’t pay much attention, only crying once at the worst of the screaming. Oddly enough, it was little Mamie who was able to calm him back down–holding him on her lap at the kitchen table with his head on her shoulder, bouncing him up and down, and murmuring quiet words of assurance in his ear. She would make a good mother in her time.

Mamie herself listened to all the goings on with her typical wide eyes. When she asked Papa what was happening, he replied that it was ‘women’s business,’ and that she would learn about it when she was old enough, just like Nona was learning now. Little Mamie resolved to ask her big sister later for more information.

Finally a baby’s first cry was heard. Papa took the kettle of hot water warming on the stove into the bedroom and when he returned, he held a baby girl, wrapped in a soft baby blanket that had been a gift at the church baby shower, to show the siblings. Mamie looked at the smiling newborn with its eyes still squeezed shut, “What’s her name?” she asked her father. We are going to call her, ‘Alice,’ he replied.

* * *

1920 JUST ONE MORE

Mama loved her new daughter, she really did, but somehow she had gotten into her mind that she should have a son to replace the one she had lost. When baby Alice was weaned, she would see if she and Papa could try just one more time…

* * *

1921 THE LAST ONE

Mama Perdue lay back after the contraction, covered with sweat and panting heavily. Nona hovered over her, white-faced with fear, sponging the sweat from her mother’s brow with a wash cloth.

Mama had been in labor much longer than ever before. She finally had agreed to send Papa to fetch the neighboring farm wife, who should be back soon…

In between the contractions, which were become more and more desperate, Mama’s neighbor pushed and felt her distended belly, pushed and felt it over and over, murmuring that the baby was turned around wrong.

Her ministrations must have corrected the baby’s position enough as it finally arrived with an extended push and a mighty scream by Mama Perdue. Afterwards, Mama fell back on her pillow, barely conscious, to the worried looks of her two attendants.

Nona lifted her mama’s head to help her drink some water. “It’s a boy,” she told her mama quietly. Mama Perdue smiled, “We shall call his name ‘Coy,’” she barely whispered the ritual words of naming.

Mama Perdue didn’t need the advice her friend gave before she went back home to know this would be her last baby. Delivering this one had almost killed her. She wouldn’t make the mistake some mothers did to try for one more child than she could safely deliver. She almost had this time. There would be no more children borne by her on the Perdue farm.